Masonry heaters gain traction for their efficiency and durability

Masonry heaters create a natural gathering place for the whole family, as shown in this Arrowsic home. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAINE MASONRY STOVES

By Justin R. Wolf

Ottavio Lattanzi built himself a saltbox house in the Midcoast town of Bowdoinham nearly half a century ago. The 1,500-square-foot home, which he describes as “pretty well insulated but not airtight,” is heated using a small masonry stove he affectionately calls his “Russian fireplace,” with a fire box measuring just 1 foot by 1 foot and 2 feet deep. That’s enough space to accommodate handfuls of kindling and the occasional small log. The firebrick-lined stove, which was custom-built by a friend from Belarus, emits radiant heat for up to 12 hours and has been the home’s sole heating source for the better part of four decades.

Masonry stoves (aka masonry heaters) have been around for centuries. Historical precedents are vast and date back millennia, from the kang, or bed-stove, in northern China, to hypocausts in ancient Rome. More contemporary examples descend from the Central European kachelofen and techniques pioneered by Germans and Scandinavians in the 19th century.

A super-efficient fire in a large masonry heater warms the surrounding bricks and mass to heat this 3,000-square-foot central Maine home. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAINE MASONRY STOVES

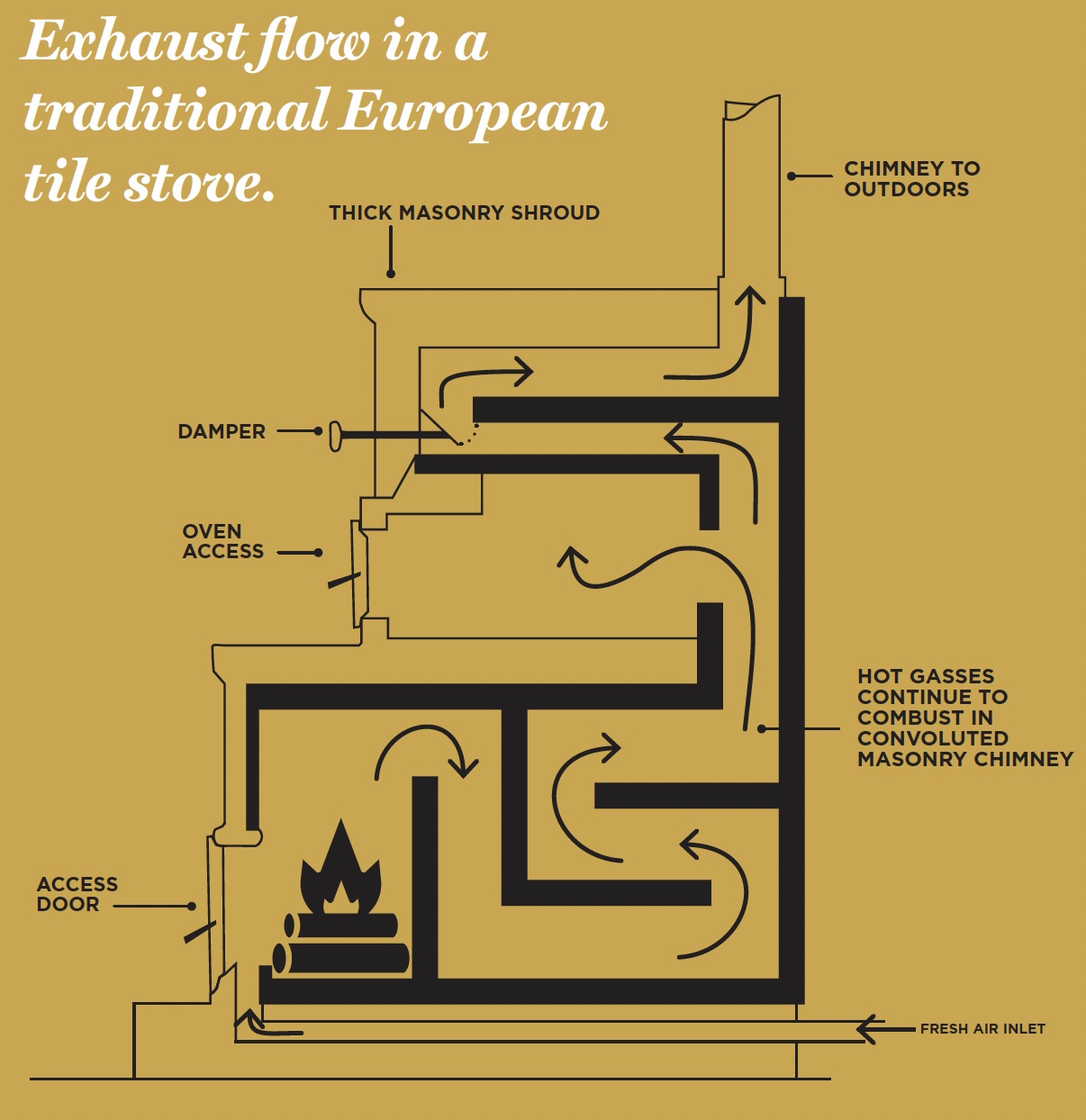

Typically composed of a firebox encased in layers of firebrick, stone, or clay, the stoves work by burning wood fuel at a rapid rate and circulating heat through internal heat-exchange flues and interconnected chambers. This allows the thermal mass of the masonry to reflect, store and radiate heat for extended periods. Unlike wood stoves made of metal, masonry heaters achieve more complete combustion, thus minimizing the emission of unburned gasses and the buildup of creosote, and they continue emitting heat long after the fire burns out.

Modern designs abound, from squat rectangles to cylindrical towers. Cladding and masonry choices, whether one opts for soapstone, ceramic tile or something else, tend to be more about aesthetics than performance. Sizing the heater to one’s home, however, is critical. Eric Schroeder, owner of Maine Masonry Heaters in Lisbon Falls, prefers an approach of “small, medium, or large.” He says, “With masonry heaters there’s a constant heat output because it’s radiant. They work great in a drafty farmhouse because you’re not heating up air that just flows out through the walls.” In such cases, Schroeder concedes the benefits of making insulation upgrades. Even if one is living in a Passive House, where a heat pump will suffice, a small, light masonry heater can be a very efficient option.

Schroeder’s approach to rightsizing is more scientific than he lets on: A blog post on his company’s website states that masonry stoves in well insulated homes should have less surface area and thinner walls. (A common wall thickness is 4-7 inches.) “You want a gentle, steady heat source that sticks around but doesn’t overheat the space,” he says.

Concerns about overheating will likely resonate with people living with cast iron stoves. Any masonry heating professional is quick to point out some key differences. “A metal box is an inherently bad way to burn wood because it transmits heat away from the fire, and the fire burns out very fast,” Schroeder says. “But if you work with a [masonry] material that can handle the heat and a buffer system that spreads that heat out over time, then you’re getting a ton more energy out of the wood.”

Given the building material, masonry heaters are several times heavier than a typical wood stove. And with good reason.

“We’re talking about a battery,” says Albie Barden, a longtime builder of masonry heaters, based in Norridgewock. In a 2023 episode of “The BS + Beer Show,” an online talk show for building science enthusiasts, Barden remarks, “You get a charge that lasts about an hour and a half, and the battery gives off heat for 10 to 12 hours, and sometimes up to 24 hours.” The resulting air, he says, feels clean, crisp and comfortable.

Masonry stoves have a modest but growing market presence in the northern United States. Options range from smaller, factory-built stoves that run upward of $8,000 and can be installed in nearly any home without additional structural reinforcements to elaborate custom builds that require installation by skilled masons and cost north of $15,000. Such costs should be considered relative to future offsets like heavily reduced energy bills and reduced need for biofuel compared to wood stoves.

For those looking to install a heater in an existing home, there are many options; from retrofitting a fireplace or masonry chimney to installing a heater with a stainless steel ventpipe. Whatever the investment looks like, masonry heaters are gaining popularity for several reasons. They are durable and hyperefficient, for starters. And for those who cherish the sight of a hearth ablaze, masonry stoves are the ideal blend of form and function.

In Bowdoinham, Lattanzi, now 75, has since installed a backup system of propane space heaters, but he maintains that his tried-and-true Russian fireplace is bar none. “It just warms everything up,” he says. “It’s a different kind of heat.”

This article appeared in the Fall 2025 edition of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES. Subscribe today!

Find Maine experts that specialize in healthy, efficient homes in the Green Homes Business Directory.