The basement myth

Basements are more complicated than most people realize. This drone shot of a basement under progress shows the amount of earthwork, formwork and thoughtful drainage needed to achieve a quality basement. PHOTO: COURTESY OF STEVE MARIN, VISION BUILDERS

Do we need basements? And if so, when?

By Chris Briley

As an architect of high- performance homes in Maine, I often find myself having a conversation about the necessity of basements. Or to be more specific, I’m often arguing that a basement isn’t necessary. For many people, this is a surprise and requires a substantial shift in mindset.

Why basements exist

Basements are a cold-climate phenomenon due to the freezing of the ground (or rather the freezing of the water in the ground). During a Maine winter, frost depth can be as deep as 4 1⁄2 feet. When the ground freezes, it will expand. If your home were to rest on that freezing soil, it would get lifted as the ground expands and fall back again as it thaws. In Maine, our soils are not homogeneous, so that expansion would happen more in some places than others. As the ground goes through its freeze/thaw cycles, the foundation would lift and fall unevenly, easily splitting a foundation wall.

To properly found your house, you must beat the frost, which usually means digging deeper than 4 1⁄2 feet and bearing on the deeper soils. This is very old building science. Our colonial predecessors had this figured out and were digging foundations deep into the ground.

Once large excavating equipment became commonplace for home construction, digging became easy. From there, it’s easy to think: if you’re digging down 5 feet, you might as well dig a few more so you can stand up in your new foundation space, your basement.

The great basement myth

This evolution of basements gave rise to the great myth about basements: Since you need a foundation anyway, a basement is practically free! This is untrue in terms of both cost to the homeowner and to the planet.

To turn the colonial basement described above into a space that keeps water out and humidity levels in check requires considerable effort and attention to detail. Making that basement a habitable, enjoyable space requires conditioning the space and bringing it into your indoor air volume. It means insulating it, adding power, lighting, and finishes, and essentially doing everything you need to do above grade. This isn’t “practically free.”

Unprogrammed space

Why do you want a basement? This is usually the start of our basement conversations. It’s a very basic question, but the homeowner will be paying for every square inch of it so they should know why. Sometimes the response is “I just assumed we needed one.” Good news: You don’t. You need a foundation, a way to soundly anchor your home to the ground. That doesn’t necessarily mean a basement. Sometimes the answer is, “That’s where all the utilities go. I don’t want that stuff upstairs with me taking up precious space.” What if the house is so energy-efficient that all the utilities you need fit in a large closet? Problem solved. Or maybe they say, “We have a lot of bulky stuff we don’t use often, and we need a place to store it.” What if we found you some dry attic space? Maybe over the garage? That would be much cheaper than a basement. Often, there’s no programmatic need for a basement; it is simply unprogrammed space (a term we use in the architectural biz for a space that is unplanned and is an incidental artifact of organizing the other spaces in the house).

Other times, however, our clients have specific uses that they have that space earmarked for, such as a home theater, wood shop, or teenager rec room. Or maybe the slope of the home site is steep enough that a daylight basement makes sense. These situations are a different story, and worth a discussion, and if we’re going to do a basement we need to make sure it’s done well. We’ll get to that in a moment, but first we need to talk about one of the major reasons to shun basements.

Basements are carbon monsters

Cement, the major ingredient in concrete, is a high emitter of CO2 and responsible for 7% of the world’s carbon emissions. That is a massive impact from just one product. As sustainable architects, we try to limit our usage of cement in our house designs as much as possible. For more perspective on this: 35% of a typical home’s up-front carbon footprint comes from the concrete basement walls and slab. If we can eliminate the basement, we can have a dramatic effect on a home’s carbon impact.

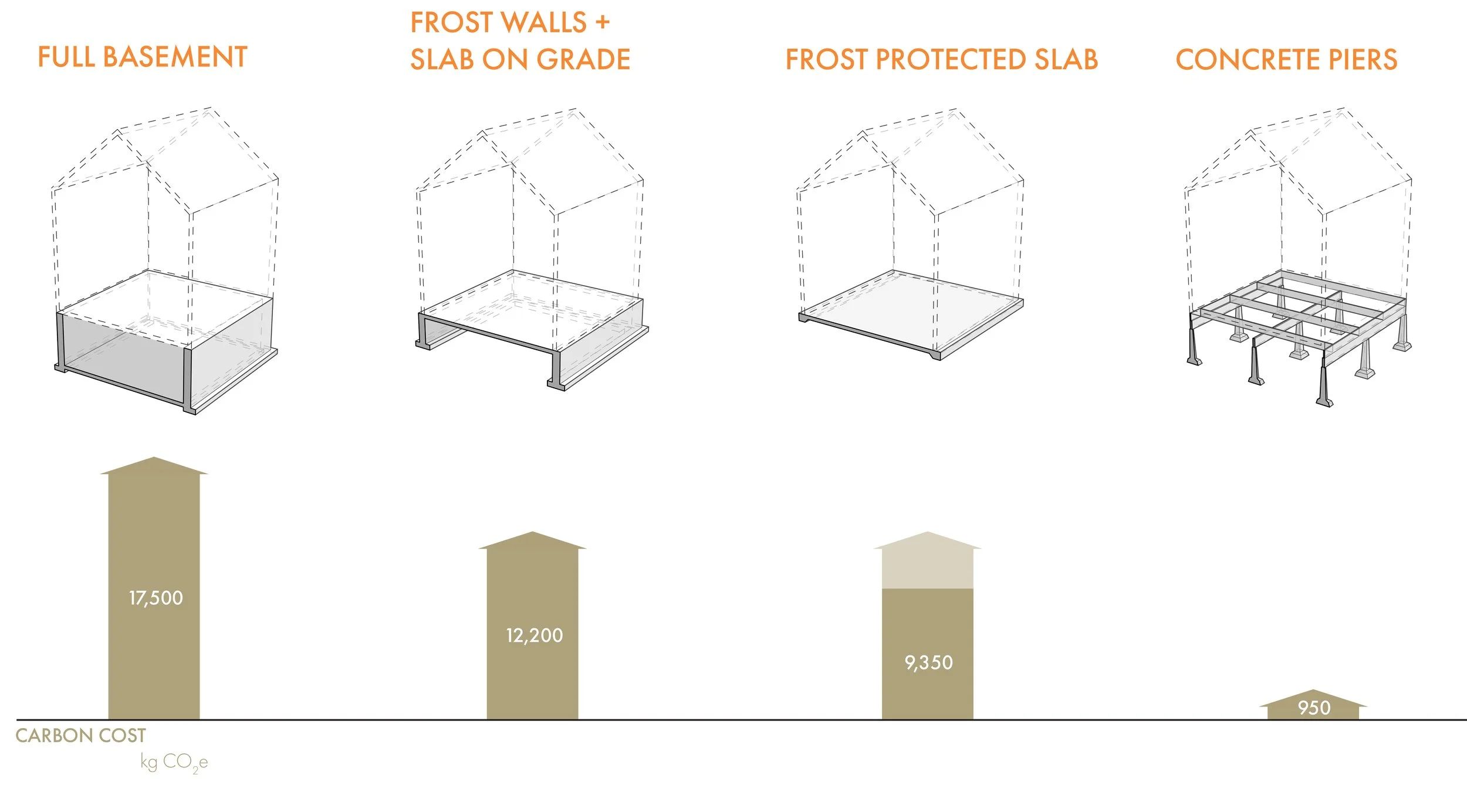

ILLUSTRATION: BRIBURN

To help illustrate this, we took a hypothetical home design of 2,000 square feet of above-grade living and modeled four different foundation methods using BEAM (a carbon calculator available free from Builders for Climate Action). As shown in the graphic, a typical basement foundation system equals 17,508 kgCO2e (kilograms of carbon dioxide, or equivalent gas). For perspective, an average American’s year of driving equals 4,000 kgCO2e in emissions. So this full basement would equal the emissions of 4.3 years of driving (if you’re an average American who commutes 26 minutes to work and gets about 25 miles per gallon on your vehicle, though I suspect you drive a hybrid, work from home, or bike in good weather).

In the second scenario, we tested a concrete frost wall with a slab-on-grade first floor. This reduced our upfront carbon emissions to 12,218 kgCO2e (the equivalent of three years of driving.)

Next, we tried a frost-protected slab. This refers to a slab that beats the frost not by digging deep but by insulating horizontally outward to allow the heat of the earth and of the occupied home to prevent the ground from freezing. The frost-protected slab resulted in further reduction to 9,361 kgCO2e (or 2.3 years of driving).

The fourth option was to switch to precast concrete piers. This brought the concrete foundation down to 948 kgCO2e (or just 3 months of driving).

Water and fighting nature

I’ve been asked by clients, “Can you guarantee that my basement won’t leak?” I usually say, “Yes, because we can get rid of it.” But if I’m not being snarky, and we already know there will be a basement for the project, I then say, “Yes, as long as I can drain the water to daylight.”

For a leak to happen: (1) Water must be present, (2) There needs to be an opening for water to pass through, and (3) There needs to be a driving force to move the water

There’s not much we can do about water being present; there’s not a spot in our state without groundwater or moisture in the ground.

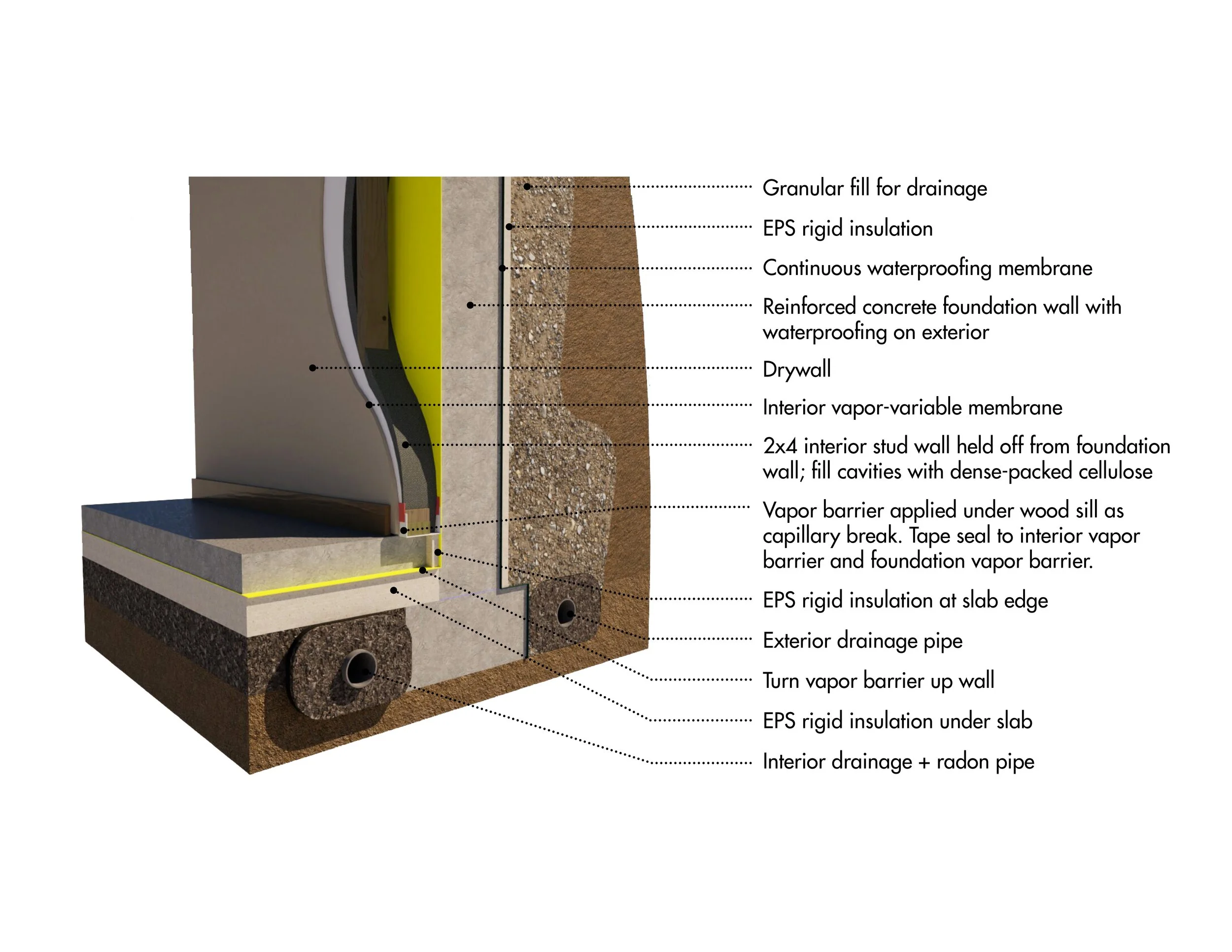

As for openings and cracks, we can address this. We will often use a fluid applied (sprayed or brushed on) waterproof membrane on the exterior of the concrete foundation wall. This needs to be properly applied and should also cover the footing. These coatings are typically flexible so that even as the concrete develops micro cracks over time (which it likely will), they can handle the slight expansion and remain watertight and continuous.

Even with our best membranes and sealers, small cracks and gaps can appear over time. So we need to also address the driving force. Imagine your basement under water, like the hull of a boat. When ground water rises or there is a major rain event, this is essentially the situation in your basement. In these situations, keeping water out is extremely difficult. Our solution then is to create a drainage path for the water and remove the driving force.

There needs to be a drainage plane against the exterior of the basement wall. Often this is created by backfilling against the foundation with a thick layer of crushed stone or gravel. As water moves through the soil, it hits this granular layer and the water drops (removing the horizontal driving force) and drains to the footing at the bottom of the basement wall. A more effective method is to use a drainage mat (or dimple mat). This membrane is usually a plastic material that has deep dimples (like an egg carton) that holds the soil away from the surface of the concrete. This has the same drainage effect. The water reaches this gap created by the dimple mat, the driving force is removed, and the water drops to the footing.

At the footing (the bottom of the wall), this water is collected by a “drain tile” system. Don’t be thrown off by the word “tile.” In the olden times, short clay pipe sections (tiles) were used to create a buried perimeter drainpipe around a home. Today, we use plastic pipe. This pipe system is installed around the outside of the house below the level of the slab. The pipes are perforated and surrounded by more crushed stone and filter fabric where ground water is to be collected, forming an underground gutter that slopes to an unperforated pipe that then drains away from the house until it reaches daylight.

ILLUSTRATION BY BRIBURN

This goes back to my comment that if I can drain to daylight, I can guarantee a leak-proof basement. But as you may have guessed, that also means the ground needs to be sloped enough around the house so that a drainpipe at the bottom of the basement can drain away from the house until it pops out of the ground. This could be over 100 feet away. What if you don’t have that kind of slope or space? Then, by choosing a basement you are choosing to fight nature for the rest of the building’s life. This means a sump (a shallow pit in your basement slab where the water can collect) and a pump that will automatically turn on when the water level rises and pump that water up and away from the house (hopefully downhill). On difficult sites where there is no convenient place to discharge water, a dry well can be used. A dry well is a large concrete cistern that is perforated on the bottom (or completely open) and filled with crushed stone. The idea of the dry well is to take in large amounts of water quickly (like from a storm surge) and let it slowly percolate back into the soil.

Insulation and humidity

Our ground is cold here in Maine. At the bottom of a basement, it’s about 50–55°F all year round—which can account for about 20% of the average New England home’s heat loss each year, according to the Building Science Corporation. It is a slow but constant drain on the home’s heat. For this reason, insulating the foundation walls of a basement is important. The 2021 IECC code (Maine’s prevailing code at the time of this writing) requires a minimum of R-10 insulation for the basement slab and for the walls; you need R-19 insulation for an interior stud wall against the concrete, or R-15 for continuous insulation (such as mineral wool boards), or a mix of R-13 stud wall plus a continuous R-5 insulation.

Though we’re all used to hearing the term “unfinished basement,” it’s no longer legal in Maine to build an uninsulated concrete wall, even if the plan is to “finish” it later. It’s just against the law and for good reason.

Insulation does more than fight energy loss. Here’s why: When a basement wall is significantly cooler than the air, there’s a high risk of condensation. Like the “sweating” cold soda can on a humid day, your basement walls can create moisture from the air and even increase the relative humidity of the whole basement. With an increase in relative humidity, there’s an increase in the risk of mold and mildew. So whether you are using an insulated stud wall on the interior, or mineral wool insulation on the exterior, it’s important for the surface of the basement wall to be above dewpoint temperature.

Interior drain pipes connect to exterior pipes to drain water, and to the radon vent to protect against radon. The yellow membrane is a vapor barrier that will seal to a similar wall membrane. It also acts as a capillary break to keep the sill dry. PHOTO: ANNA HEATH

Health and safety

Reducing mold and mildew risk is a top priority for health and safety, but basements also pose an added risk with radon. Radon is a radioactive gas produced by the decay of uranium and thorium in the earth’s crust. It’s odorless and invisible and, in high enough concentrations, it’s a carcinogen. Radon is a very small but dense molecule so it is more difficult to seal out than one might think. When it does get in, it tends to lay low; a good rule of thumb is that radon levels halve with each story above grade.

Maine has a high occurrence of radon, and there’s no way to know if you have a problem until after the home is built. In Maine. we always need to address this issue whether we have a basement or not. But as we dig deeper into the soil and even blast our way into solid ledge to accommodate our lower levels of living, the risk of radon increases. It’s imperative that a radon mitigation system be installed during construction. This usually consists of a series of perforated pipes in a crushed stone bed under the slab that are tied to an airtight pipe that vents directly to the exterior of the house. In most cases, this passive vent is enough of a pathway to mitigate subterranean radon gas, but if testing shows that there is still a problem, an in-line vent can be added to the vent stack to depressurize the sub-slab region and “power vent” the radon out.

Another aspect of a basement that sometimes gets overlooked is egress. You might be tempted to use your finished basement as a bedroom. It’s important to keep in mind that a bedroom needs two means of escape. One would be out the door and up a legal set of stairs; the other is usually out of a window with an egress-sized opening (5.7 square feet with a minimum width of 20 inches and a minimum height of 24 inches per International Residential Code). High basement windows that you’re used to seeing in old basements don’t cut it. Those windows need to be not only egress-sized but no higher than 42 inches from the finished floor.

Final argument

If you’re building/designing a home, you can avoid many issues related to water intrusion, humidity and up-front carbon by not having a basement. Also, basements are not free. In fact, they can be thought of as expensive for the quality of space they can often provide. If you choose to have a basement, do so knowing the financial and global impact of it, and hopefully it is for a space that you really need and want. And of course, be sure your design/build team addresses bulk water, moisture, humidity, insulation, radon and egress issues with skill and tenacity.

This article appeared in the Fall 2025 edition of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES. Subscribe today!

Find Maine experts that specialize in healthy, efficient homes in the Green Homes Business Directory.