Historic and Modern: Bethel landmark transformed into high-performance homes

By June Donenfeld

Photos courtesy of Northern Forest Center

On an early summer day, a group of 50 (give or take) gathered for a ribbon-cutting ceremony in front of the Gehring House, an immaculately restored 19th-century home in the village of Bethel in Western Maine.

The sky was overcast, but the mood was upbeat, to celebrate the reincarnation of a beloved local landmark as a stunning nine-unit apartment building. The Gehring House now gleams with oxblood red paint in a nod to the original dwelling, and has intricate white trim, an imposing turret, a portico flanked by Corinthian columns and a facade punctuated by 88 original windows that let the light pour in. The building provides much-needed year-round rental housing, with six 1-bedroom units, two 2-bedroom units and one studio.

Nestled on the northeastern edge of the White Mountain National Forest, Bethel boasts abundant natural beauty, four season outdoor activities, classic New England architecture and a vibrant, walkable downtown lined with independent shops. All this has made the town an enormously appealing place to work and live. Yet with vanishingly few year-round rentals of any sort, let alone for people with median incomes, current and prospective residents have been stymied by the housing crunch found across the state—and the country.

The Gehring House of today is a far cry from the sadly neglected sleeping beauty it had been for many years, despite its storied history and place on the National Register of Historic Places. Built for Dr. John George Gehring and Mrs. Marian True Gehring in 1896, the stately home served as both home and clinic, where hundreds of patients from around the U.S. were treated for stress, anxiety and depression, including well-known writers, academics, philanthropists, politicians and socialites. The clinic closed when Dr. Gehring retired in the late 1920s, and after the couple died, the building changed hands several times. By 2009, it lay empty, prey to vandalism and harsh weather.

But then the not-for-profit Northern Forest Center (NFC), a regional innovation and investment partner, stepped in. Their programs focus on strengthening rural communities, economies and forest stewardship through projects in the immense forest covering northern Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and New York. The Center had already successfully retrofitted dilapidated buildings in Millinocket and elsewhere and saw beyond the once-elegant Gehring House’s boarded-up windows and overgrown 10-acre plot to its great potential. In 2022, the Center purchased the property for $1.85 million. Construction began in 2024, and the building was ready to welcome tenants, as planned, in mid-2025.

Bethel's Gehring House now hums with life again, after an all-hands-on-deck restoration and conversion that came in on time and budget. Directly behind the majestic building, walkers, runners, mountain bikers and Nordic skiers have easy access to Inland Woods + Trails’ vast downtown trail system. It's also just a short walk to Bethel’s downtown and schools.

The Center spent another $4 million on redevelopment, drawing on varied funding sources, including impact investments, grants and individual donations. “Private developers can’t bring in philanthropic dollars,” says Amy Scott, a Maine-based program manager for NFC. “We did have low interest, long-term loans, but we also needed a philanthropic piece to make the funding structure work.”

Historic preservation tax credits from the National Park Service were also vital to bringing the project in on-budget, so there were restrictions on what could—and could not—be done. A historic preservationist deemed all the original singlepane windows salvageable, for instance, so they could not be replaced with sturdier ones. Nor could a solar array be installed on the roof or grounds, as it would have been at odds with the property’s original character.

The new apartments feature historic woodwork and refinished original wood flooring; many also feature non-operable, decorative fireplaces, notable for their beautiful period details. During the restoration process, the construction crew reclaimed 14,900 original pieces of woodwork, including sills, banisters, trim, doors, and columns, along with more than 6,400 square feet of the existing maple, birch, oak, and pine flooring. When floorboards were beyond repair, new ones were purchased from Maine-based Hancock Lumber. Because trees are renewable, hardwood floors outcompete common alternatives like linoleum, vinyl, and carpet in carbon cost and sustainability.

Among the many goals NFC had for this project were reducing its carbon footprint, employing area tradespeople, sourcing materials locally, and taking what the Center calls a wood-first approach.

“Our mission as an organization includes promoting forest stewardship and supporting wood products businesses,” says Maura Adams, director of community investment. “It’s only natural that we would try to incorporate these program areas into our housing work as well. Wood stores carbon, decreases fossil fuel and petroleum product dependence and creates beautiful and heathy spaces for residents.”

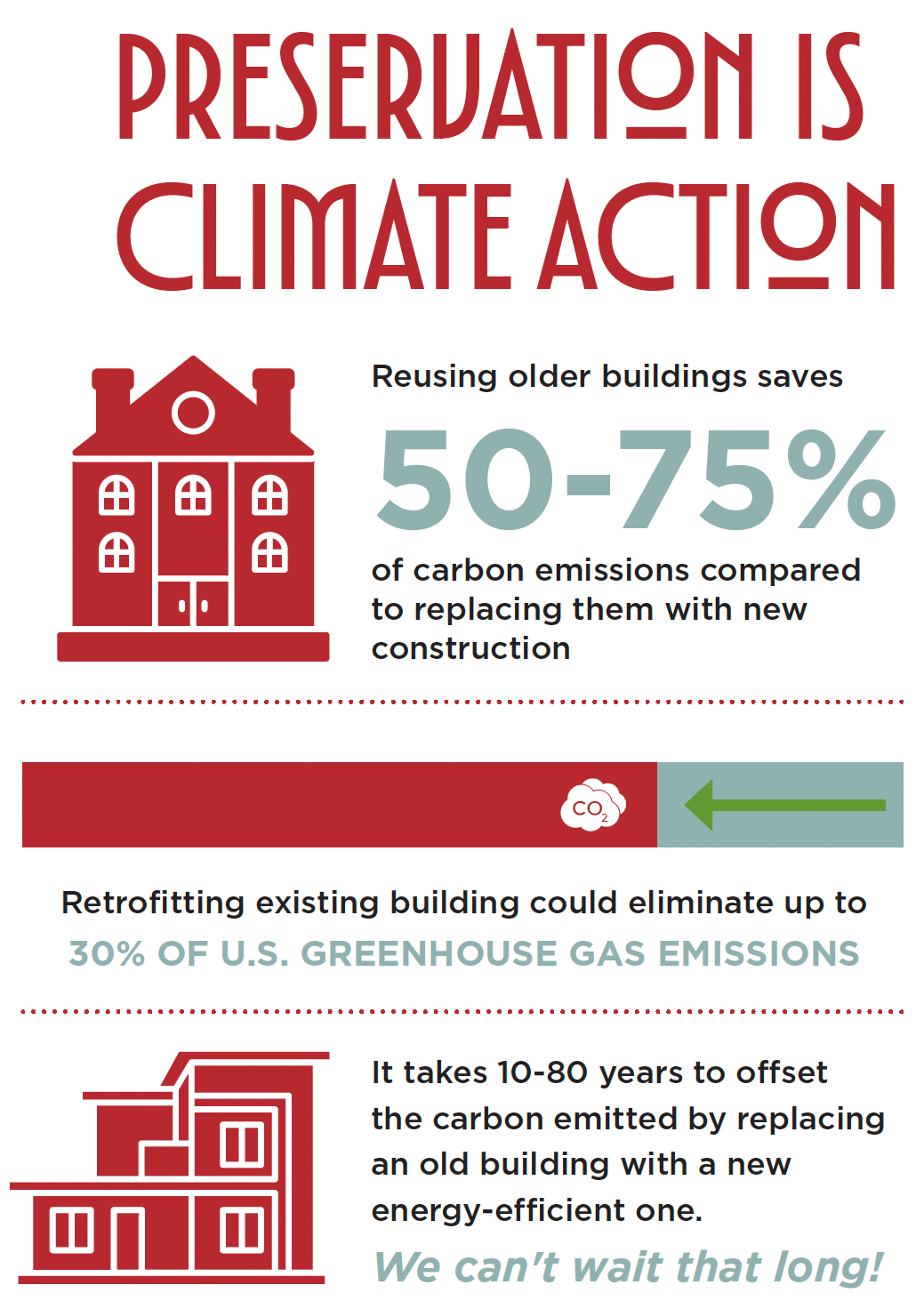

Illustration based on a graphic developed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Preservation Priorities Task Force/National Preservation Partners Network.

This approach entailed salvaging as much of the original wood as possible, using new wood as needed and installing wood fiber insulation batts from TimberHP, manufactured just 73 miles away in Madison. For the primary heating system, oil was banished and replaced by high-efficiency, automated wood pellet boilers from Bethel company Maine Energy Systems, reducing the building’s carbon dioxide emissions by more than half. Combine this with all-electric kitchens and heat pumps for cooling and supplementary heat, and all the building’s energy needs are met without a drop of fossil fuel.

The Center kept scrupulous track of carbon savings by all these, and other, measures, using an online electronic tool called the BEAM Estimator (Building Emissions Accounting for Materials), from social enterprise Builders for Climate Action. Among other outcomes, the Center reports that the reclaimed floors and locally sourced new wood alone will store enough CO2 to offset the emissions from burning 1,800 gallons of gasoline for the life of the building.

To achieve their many aims, the Northern Forest Center needed a collaborative, experienced partner that understood and supported their goals. They found that partner in Woodhull, a Portland residential and commercial architecture, building and millwork firm well-versed in high-performance building—and with historic preservation experience.

With so many must-haves and moving parts, the renovation and conversion posed some novel problems for the design and construction teams. “The multifaceted nature of the project was a new challenge for us,” says architect Anna Pajulo. “Not only were we renovating an old mansion in accordance with historic rehabilitation guidelines but also creating apartments that needed to meet modern code and energy efficiency requirements, as well as our own goals for quality design, sustainability and budget.”

This proved to be a delicate balancing act. “Since we were trying to keep as much of the original building as we could, locating new walls and running all new infrastructure for the units without disturbing or damaging existing historic elements was quite the puzzle,” Pajulo says. But solve it they did. “We were very protective of our main goals for good, healthy, functional design, sustainability, and restoring and safeguarding the historic character of the building, and thanks to … everyone on the project team, we did not need to compromise on any of these core priorities.”

Experienced hands carefully insert wood insulation from Maine's TimberHP into place, where it will help muffle noise and provide warmth.

Construction also came with its fair share of challenges, from waterproofing the fieldstone foundation to bolstering the sagging turret to recreating historic details like column capitals and rosettes. “We had the capitals made at Saco Manufacturing & Woodworking, a company specializing in wood turning since 1872,” says Michael Cleary, Woodhull’s director of commercial construction. “And the rosettes were made in the 3D printing lab at Gould Academy, just a quarter mile down the street from the Gehring House.”

Woodhull was also tasked with converting former attic space into comfortable living quarters. This called for insulating and venting the roof structure with a thermal envelope of blownin cellulose, a vapor-permeable membrane and a ventilation louver, a combination that both meets current building codes and adheres to historic preservation rules. Two large energy recovery ventilation (ERV) units in the basement bring in a constant supply of fresh air throughout the building and also help ensure that the structure will not be subject to damaging moisture.

The Woodhull team learned much from the Gehring House redevelopment they feel could be applied to similar projects. “Maine has so much great old building stock, and its preservation and restoration both celebrates our state’s past, while helping to alleviate its current housing crunch,” says Cleary. “With each renovation we complete, we learn more about how to improve on the next.”

The reborn Gehring House not only provides desperately needed rental housing but, like other adaptive reuse projects, has also likely achieved important carbon savings over standard new builds (see sidebar), even as it has strengthened the economic and social fabric of its community. But there is still work to be done at 70 Broad Street in downtown Bethel. The remaining eight acres will eventually be the site of new homes, as sustainable and welcoming as the grand dame that will be their neighbor.

Forging partnerships, investing locally and building homes across New England

The Northern Forest Center has other housing projects in the works in Maine, like a mixed-use commercial and residential building in Millinocket, where Baby Ruthie’s, an ice cream takeout and restaurant, is already open for business and a Wabanaki Youth and Cultural Center is nearing completion. And downtown Greenville will be home to NFC’s first new housing project, where they bought five acres of land and plan to build 29 units to serve the local workforce, with a mix of multi-family dwellings, duplexes and single-family homes that will be a showcase for the economic and environmental benefits of mass timber construction. In other states in the Northern Forest region, NFC housing projects are complete, in progress or planned. Lancaster, New Hampshire is home to the historic Alfred J. Noyes building, transformed into six beautiful apartments. Saint Johnsbury in Vermont will see its 1909 historic armory (and former community dance hall) redeveloped to create new high-quality housing, arts and commercial space. And construction is underway in Tupper Lake, New York, on a nine-unit apartment building and a single-family home.

PROJECT TEAM:

Architecture and Construction: Woodhull | woodhullmaine.com

Engineering: Haley Ward | crossexcavation.com

Lumber: Hancock Lumber | hancocklumber.com

Painting: Clean Cut | cleancutpaintingcompany.com

Woodwork: Wentworth Woodworking | wentworthcustomwoodworking.com

Roofing and Siding: Western Maine Roofing | westernmaineroofing.com

This article appeared in the Fall 2025 edition of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES. Subscribe today!

Find Maine experts that specialize in healthy, efficient homes in the Green Homes Business Directory.