Welded bliss

Pownal couple joins a metalworks business with a homesteading lifestyle.

As a nod to his metalsmithing business, Nicholas Cote built one of the retaining walls in his terraced mountainside garden of weathering steel.

BY AMY PARADYSZ

IMAGES: JENNIFER BAKOS PHOTOGRAPHY

When the owners of Bradbury Mountain Metalworks first met, it didn’t take long for them to realize they shared a do-it-yourself philosophy of reducing their impact on the environment.

“We both like putting in a really hard day’s work, and there’s something to be said for creating things yourself,” says Heidi, who met Nicholas Cote online in 2009. “We were talking on our second date, and I said that it would be fun to live off the grid and build a house from scratch, and I think he found that very attractive.”

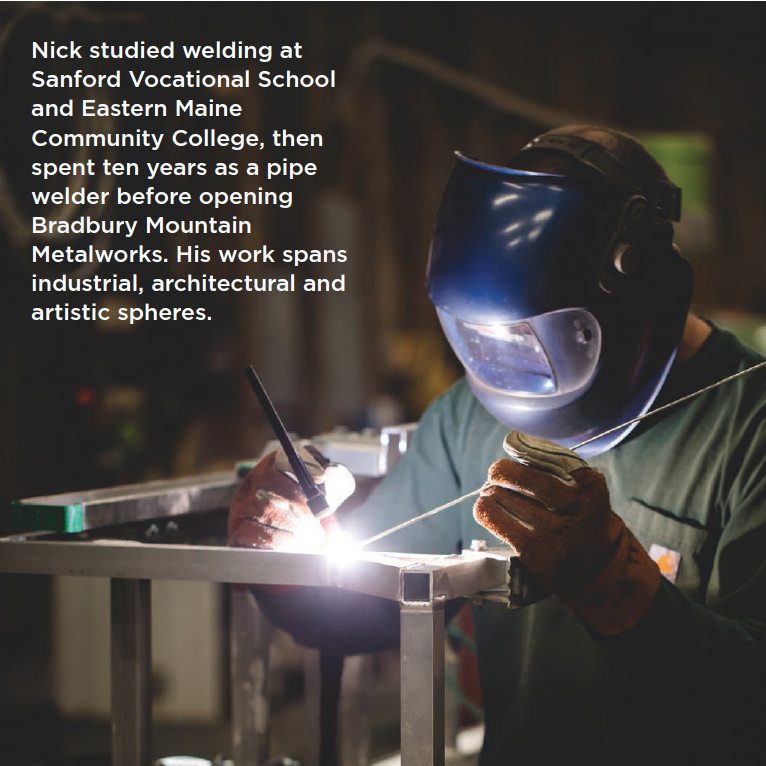

Nicholas had already fallen in love with welding when he was 16 and learned how to make himself a trailer for his snowmobile. “It’s the satisfaction of making something that is strong and will last for a long time,” he said. After studying welding at Sanford Vocational Technical School and Eastern Maine Community College, he spent more than a decade as a pipe welder, always dreaming of opening a metal fabrication shop.

The oversized mailbox at the bottom of the hill is a replica of the Bradbury Mountain Metalworks shop.

It took the Cotes two and a half years to find the right piece of property for both a home and business, somewhere rural near protected recreational land but not too remote for customer visits. In 2012, they found land in Pownal abutting Bradbury Mountain State Park on the end of a dead-end dirt road but just minutes from Freeport and the interstate.

The property included two buildings: a garage that had been built to house an antique fire truck, and the shell of a 16,000 square-foot barn-style structure that had once been a hobby sawmill.

The Cotes transformed the garage into a cozy cabin, first stripping it down to the framing, replacing the garage door with French doors and milling wood to build a lean-to addition for a bathroom and utility closet. The rest of the 600 square-foot cabin is one room, two walls covered with old barn board from a demolition project. The countertops are live-edge pine boards. Nicholas and his stonemason grandfather, Leon Tanguay — then 90 — did the stonework behind the fireplace.

Between Craigslist and the Habitat ReStore shop in Portland, the Cotes found a second-hand refrigerator, gas stove, washer, dryer, tub, sink, toilet, cabinets, doors, windows and bathroom tile. The bathroom vanity and medicine cabinet came from the basement of Heidi’s childhood home. They got everything except their mattress second-hand.

“When stuff still works, I don’t think it should be thrown out,” she said. “If people think about their impact and minimizing their impact, you can find stuff that works and is pretty cool.”

The Cotes heat almost exclusively with wood — 1½ to 2 cords per winter — though a gas-powered radiant floor takes the chill off in the bathroom during the dead of winter.

After completing the cabin, they turned their attention to the 1,600-square-foot former sawmill. They replaced most of the roof and reused the old metal sheet roofing on the walls and ceiling of a metalworks shop where sparks fly. For the exterior of the workshop, the Cotes cut and milled logs in a board-and-batten style and used a natural Japanese wood-burning technique called shou sugi ban to blacken and preserve the doors.

By August 2017, Bradbury Mountain Metalworks was open for business, with commissioned steel and aluminum projects as varied as sliding barn doors, retaining walls, staircases and handrails, table bases, fire pits, hydrologic log handling components and decorative sculptures. The work spans industrial, architectural and artistic spheres, with one of the more memorable commissions being the base for a large work of sculptural art.

“Typically, a customer will present me with a problem and I have to come up with a solution and a design,” Nicholas said. “I like that part of it, thinking about how to assemble something and how to cut it.”

As part of their commitment to reducing their environmental impact, the Cotes went solar as soon as the business was established enough to afford a solar array. In the fall of 2019, they hired Maine Solar Solutions to install an 18-panel array on the roof of the workshop — with plenty of room to add more as business needs warrant. The array generates just a smidge over 100 percent of their current energy usage, completely covering the monthly power bill of $120–$140 for the business and home combined. With a tax rebate, a possible $2,500 Rural Energy for American Program (REAP) grant, and the price of electricity rising about 3 percent a year, Nicholas estimates that the $18,000 up-front investment will pay for itself in seven or eight years, after which they’ll enjoy decades of free energy. The environmental rewards are more immediate.

“A typical residential solar panel system will eliminate three to four tons of carbon emissions each year, the equivalent of planting more than 100 trees a year,” said Heather Hodgkins of Maine Solar Solutions. “The Cotes’ panels are warrantied to produce a certain amount of power for 30 years, which would mean that at the end of the warranty they would have planted almost 3,000 trees. Talk about an impact.”

The Cotes hope to grow as much food as they eat. Beyond the terraced garden, as shown last fall, they have built a greenhouse on the patio. The 3,000-gallon plastic water tank will collect runoff to be used for watering crops.

REAP encourages small businesses and agricultural producers to invest in renewable energy. Hodgkins got to know the Cotes as she helped them through the extensive process of applying for a REAP grant, inventorying everything they own that can be plugged in to demonstrate that more than half of their electricity use is for business purposes.

“Their solar array produces 7,545 kilowatt hours a year,” Hodgkins said. “Interesting, because this is what we consider a standard array size for an average home. Pretty impressive considering he runs a metalworking business.”

Heidi and Nicholas Cote, owners of Bradbury Mountain Metalworks, believe that their welding and fabrication shop is the first in Maine to go solar.

In the Cotes’ case, all their home appliances are apartment-sized and high-efficiency, and they have chosen to not have a home computer or television.

“We try to be deliberate in our choices around what we need versus [what we] want to live comfortably,” Nicholas said.

“It’s hard for some people to believe that anyone lives that minimally, but they do,” Hodgkins said.

With the solar project done, the Cotes are in the middle of several projects related to food production. “To be completely self-sustainable isn’t feasible, but we like the idea of growing as much food as we eat,” Heidi said, adding that they both went vegan last year.

The Cotes have transformed the heavily sloped land behind their cabin into terraced garden plots, where last summer they harvested potatoes, peas, onion, tomatoes, peppers, broccoli, wild blueberries and raspberries that are indigenous to the Pownal area.

To extend the growing season, the Cotes took a class from the Shelter Institute in Woolwich, then built a post-and-beam frame for a greenhouse attached to the workshop. They installed a ground-to-air heat transfer system that pushes warm air down into the earth, insulates it and sends it back up again when the temperature drops.

Next, Nicholas made a root cellar, welding a marine shipping container to make it structurally safe to bury.

To guard against depleting their well when watering their large steppe garden, the Cotes plan to add gutters to the roof of the workshop and funnel rainwater into a 3,000-gallon plastic water tank. The tank will be partially buried, covered and cedar shingled to look like an old-fashioned water tower.

“One of our goals is to do it — whatever it is — when we can pay for it. It’s a different way of thinking about things, but it’s doable,” Heidi said. “Our home and business are completely paid off.”

Even with so many professional and personal projects in the pipeline, the Cotes make frequent use of Bradbury Mountain State Park — mountain biking, fat-tire biking, hiking and snowshoeing, often with their dog, Beara.

“It works out that our house is so small, because we don’t spend a lot of time in there,” Nicholas said. “By being conscious of our choices, we aim to have less negative impact on the environment for which we care deeply.”

This article first appeared in the Spring & Summer 2020 issue of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES magazine. Subscribe today!