Climate Action Plan looks to the future of Maine buildings

By Scott Gibson

As the White House refocuses the country on combating climate change, Maine is developing an ambitious plan of its own to cut greenhouse gas emissions and become a carbon-neutral economy by mid-century.

Legislation creating the Maine Climate Council was signed into law in 2019, and in December 2020 the group published the Maine Climate Action Plan, a four-year blueprint to push the state toward its emissions targets—a 45% decrease in greenhouse gas emissions by 2035, a reduction of 80% by 2050, and carbon neutrality by 2045. “Maine can’t wait to heed the warnings of scientists who tell us we cannot delay reducing carbon emissions to stem climate impacts,” Gov. Janet Mills writes in the introduction to the report.

The “Maine Won’t Wait” plan, written by working groups of government and industry experts, will need support from state lawmakers in the form of legislation and money to turn these initiatives into reality. That process got underway when the new session of the Legislature got to work in January.

Upgrades to buildings, which are currently responsible for about one-third of Maine’s greenhouse gas emissions, are detailed in one of the report’s eight main chapters, or strategies. Resilient communities—meaning communities that can cope with the effects of climate change—are covered in another, while transportation and renewable energy sources in others.

What kind of future does the plan see for residential and commercial buildings in Maine in the decades to come? How will these strategies—assuming they become law and get enough funding— change how we heat and cool the houses that we have today? And how will these goals affect the kinds of houses that are built in the future?

Changes in housing and construction practices won’t be immediate. Instead, the Climate Plan lays out recommendations on Maine’s new and existing housing stock that will, over time, make housing more energyefficient.

Here are some of the key goals:

Install at least 100,000 new heat pumps by 2025.

Double the rate at which existing houses are weatherized. At least 17,500 additional homes and businesses should be weatherized by 2025. This includes at least 1,000 low-income households per year. By 2030, at least 35,000 homes and businesses should be weatherized.

By 2024, develop a long-term plan to phase in more stringent energy codes for new construction. By 2035, all new buildings should be net-zero in emissions. Contractors and code-enforcement officers should be better educated. Develop building products that produce fewer emissions and take advantage of Maine’s forestry resources, such as wood fiber insulation and mass timber components that can replace carbon heavy steel and concrete.

Promote more efficient public buildings.

Get hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants off the market by next year. HFCs are widely used in manufacturing insulation, among other things, and have a global warming potential hundreds of times higher than carbon dioxide.

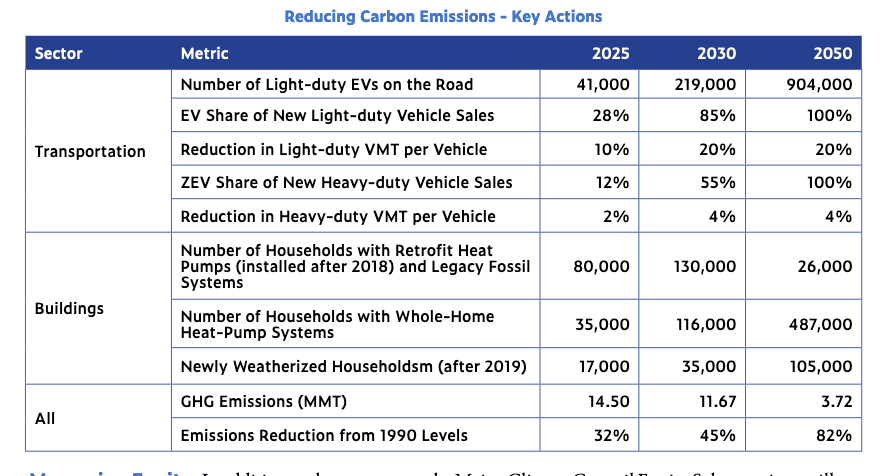

Maine’s Climate action plan envisions more electric vehicles, more heat pumps and increased weatherization of existing houses as part of a strategy to lower carbon emissions over the next several decades.

VMT= Vehicle Miles Traveled

MMT= Million Metric Tons

EV= Electric Vehicle

ZEV= Zero Emission Vehicle

GHG= Greenhouse Gas

HEAT PUMPS ARE KEY TO EFFICIENCY GOALS

The report pins high hopes on heat pumps, electrically powered appliances that don’t directly burn any fuel. Steady technical improvements over the past decade have made heat pumps efficient even in temperatures well below zero. Heat pumps also can run in reverse and cool an interior space in summer, making a separate AC system unnecessary. When the source of the electricity that runs them is clean—not derived from fossil fuels—heat pumps mean much lower greenhouse gas emissions. Maine is fortunate to have one of the cleanest electricity supplies in the country. In 2019, 80% of Maine’s net electricity generation came from renewable resources.

About 60% of Maine households now use heating oil as the primary source of heat—the highest percentage in the country, according to the report. (A single oil-fired boiler burning 750 gallons of oil a year would produce more than eight tons of carbon dioxide.) Another 12% of Maine households use propane, which is cleaner than oil—but marginally. With financial assistance from Efficiency Maine, more than 60,000 high-performance heat pumps (and 35,000 heat pump water heaters) have been installed in Maine over the past several years. The Climate Plan suggests another 100,000 heat pumps be added over the next four years. At a cost of between $2,500 and $5,000 each for an installed heat pump, the total investment could be between $250 million and $500 million. But the push, and the investment, is justified, says Jesse Thompson, a Portland architect and a member of the Climate Council’s Buildings, Infrastructure & Housing working group.

Maine is heavily reliant on heating systems powered by fossil fuels. This steam boiler, which heats a 1,400-square-foot home, will use about 750 gallons of fuel oil in an average winter. The Maine Climate Plan envisions a move toward electrically powered heat pumps to lower carbon emissions. Photo: Scott Gibson.

“One of the things that stood out so clearly is that Maine’s climate problem is different than other states,” Thompson says. “It’s vehicles, transportation, petroleum and the fuel oil in people’s houses. Those are the hugest climate emissions by far. When you stare at that, you say, ‘We’ve got to get the oil boilers out fast,’ and how do you do that? You do that with heat pumps.”

When the group looked at where money has been spent in the past and what were the most effective ways of cutting carbon emissions, Thompson says, the payoff from using heat pumps is obvious.

“Every dollar you put into a cold climate heat pump saves Mainers huge money, and it saves huge amounts of carbon,” Thompson says.

It’s not a given that each of the 100,000 new heat pumps will come with some financial incentive from Efficiency Maine or another state agency, says Michael Stoddard, executive director of Efficiency Maine and a member of the full climate committee. As an example, he noted the rising popularity of LED light bulbs. Incentives helped consumers buy their first LED light bulbs, Stoddard says, but they kept buying them because they liked the performance.

“The same thing is true with heat pumps,” he says.

Stoddard says that funding sources have already been identified to help the state reach the 2025 goal. Sources for grants and rebates include the ISO-New England Forward Capacity Market, conservation funds paid by electricity ratepayers, federal funds and settlement funds from the New England Clean Energy Connect project. The challenge is what happens after that.

“That’s where there’s more work to do,” Stoddard says, “but I would submit that it’s not by financial incentives alone. They are a piece of the puzzle, but they are not the only piece.”

WEATHERIZATION BUT NOT DEEP ENERGY RETROFITS

Reducing carbon emissions from the 550,000 existing homes in Maine is a big part of the challenge. The climate plan addresses this not only with increased numbers of heat pumps but also by doubling current rates of weatherization, a process in which air leaks are reduced, insulation is increased and lighting and appliances are upgraded. Weatherizing 17,500 additional homes and businesses by 2024 would mean another 4,300 buildings with lower carbon emissions per year—1,000 of these upgrades earmarked for low-income households.

Dan Brennan, director of the Maine State Housing Authority, says his agency spends about $3 million a year in federal funds for weatherizing the homes of low-income families and can upgrade 750 homes per year. Separately, Efficiency Maine is currently spending about $3.5 million a year on weatherization programs. As the program ramps up, carbon emissions will fall, but both Brennan and Stoddard say that developing and maintaining a labor pool to do the work will be critical to the program’s success—and that takes consistency.

“It’s not helpful to businesses that are hoping we provide services for many years if you’re just going to yank the rug out from underneath them two years later,” Stoddard says.

More extensive upgrades to Maine’s existing housing stock—what are called “deep energy retrofits”—often include new high-performance windows, exterior insulation and rigorous air sealing. Deep energy retrofits have the potential to transform an average house into a net-zero house, but the process can be expensive and time-consuming.

“We see the retrofit problem as a problem that’s not been solved,” says Naomi Beal, executive director of the non-profit passivhaus Maine and a member of the buildings working group. “We don’t really understand how to do it.”

High-performance houses, like this double-stud wall home built by Kolbert Building, will lower greenhouse gas emissions in the future. Maine’s existing housing stock poses another challenge for reducing energy consumption. Photo: Scott Gibson.

MAKING NEW BUILDINGS BETTER PERFORMERS

Although the number of existing homes dwarfs the 5,000 to 7,000 annual housing starts in Maine, the efficiency and carbon footprint of new houses certainly counts. Stricter building codes are the principal tool here for lower emissions, and Maine is still playing catch-up.

Without offering any specifics, the report suggests that by 2024 a long-term plan “to phase in modern energy-efficient building codes” should be developed, with the intent to reach net-zero carbon emissions for new construction by 2035. There has been recent progress on that front: in particular, a state law passed in 2019 requiring the state to use the most recent or the second most recent versions of the codes published by the International Code Council. The two key codes for residential construction are the International Residential Code (IRC) and the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). Both are updated every three years, with energy provisions such as insulation and airtightness getting progressively more demanding.

More stringent building codes requiring high levels of insulation and better windows will eventually help lower carbon emissions, but progress is slow. Maine only recently upgraded to the 2015 International Energy Conservation Code and is still two code cycles behind. Photo by Scott Gibson.

The Maine Universal Building and Energy Code (MUBEC) has recently been updated to include the 2015 version of the IECC (up from the 2009 IECC), and the state now permits municipalities to adopt a more stringent “stretch code” in the form of the 2021 IECC. But towns with fewer than 4,000 people are still not required by law to enforce the code.

Nationally, code updates are a battleground pitting industry trade groups such as the National Association of Home Builders against advocates for greater energy efficiency. Some builders, especially owner/builders, don’t like being told what do to. Municipal inspectors are sometimes shocked by buildings that are “structurally terrifying,” Thompson says, and there’s often a pushback when more stringent building codes are proposed.

“That mood is out there,” Thompson says. “But every single time anyone ever does an economic survey of building codes the argument is so clear that the codes save people tons of money. They save the consumer tons of money. And the only people who don’t want to do them are the low-end builders.” Stoddard, who is a member of the MUBEC board, says it will take time to get building inspectors and builders up to speed on what more stringent codes require, but once the current set of codes is understood and folded into the system, change in the future should be smoother.

When it comes to multi-family projects financed through the Maine State Housing Authority, Brennan says his agency is encouraging more energy-efficient designs without requiring something as far-reaching as Passive House design. Setting unrealistic requirements for builders, he says, encourages a “points for promises” scenario where developers seeking tax credits to finance their projects promise more than they can deliver.

“The key is to have a balance between mandating something that someone is not able to achieve and incentivizing those who can achieve it,” he says. “We keep moving the ball in that direction every year.”

This affordable housing project designed by Kaplan Thompson Architects in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood combined high-performance windows, advanced air-sealing techniques, and a super insulated building enclosure. Carbon emissions will be substantially lower than in a conventionally-built project, but Passive House quality projects like this one are not the norm. Photo by Scott Gibson.

THIS CLIMATE PLAN IS A FIRST STEP

Builders, architects and public officials who took part in developing the Climate Action Plan say they are encouraged with progress to date, but they also recognize the plan is not completely formed. It’s a four-year step in a much longer process.

“It’s such a massive problem,” Thompson says. “Will all the efforts be enough? How could they ever be enough? We’ve waited a little too long to get our act together. But it’s a serious effort, and people put a lot of energy into it, every idea they could. I think that’s worth praising.”

Brennan put it this way: “I think one of the beauties of the plan they put out is that it’s manageable. This is a four-year action plan. At the end of the four years, are we going to be done? I don’t think so. What [commission cochair] Hannah Pingree and her team and all those folks did is come up with something that’s manageable, that’s achievable, that we can get done in four years. And then it becomes a lot more real. It will lay out the framework for what needs to be done in the four years after that. And the four years after that.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2021 edition of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES. Subscribe today!

Find Maine experts that specialize in healthy, efficient homes in the Green Homes Business Directory.